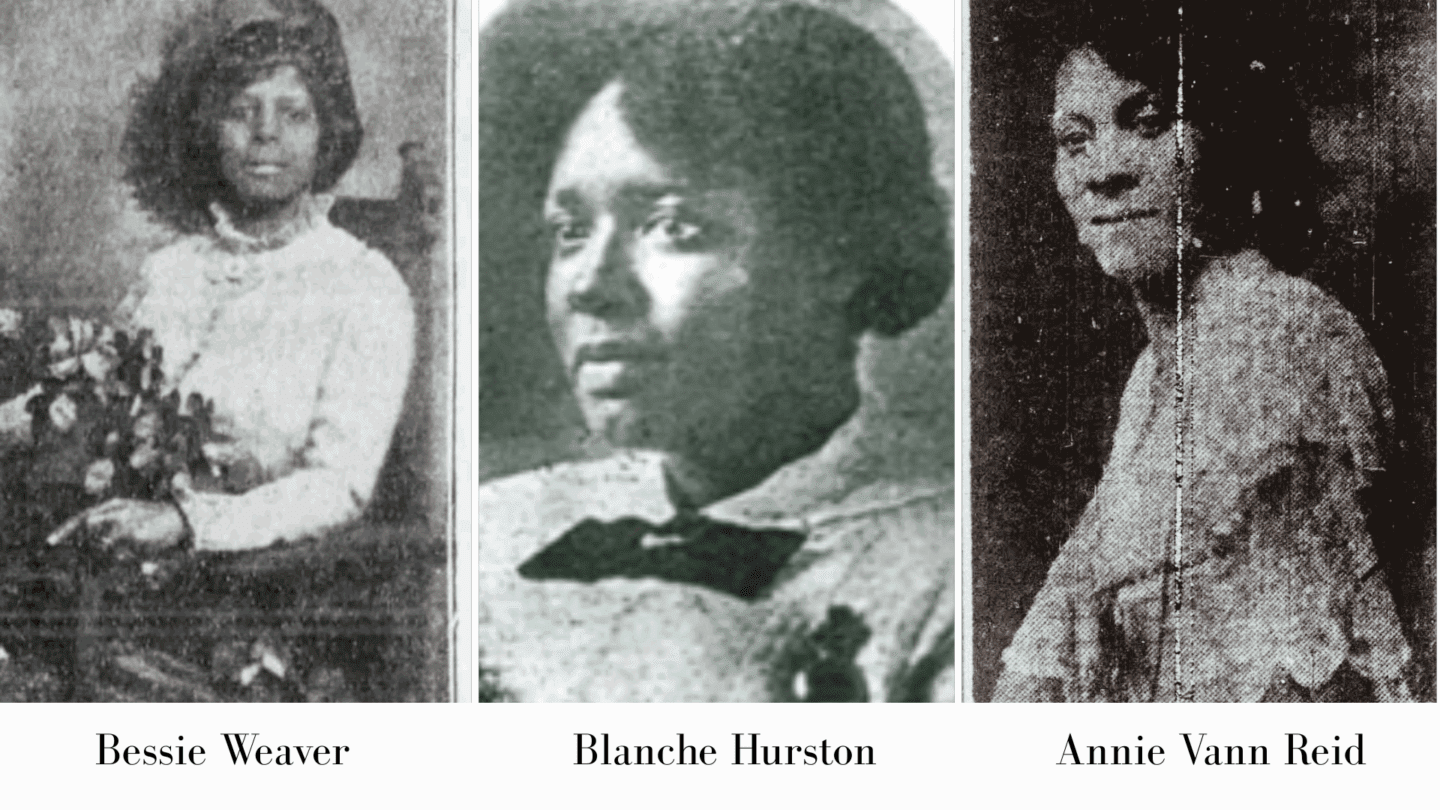

In 1915, Kansas City (Missouri) floral shop owner and floral designer Bessie M. Weaver addressed Booker T. Washington and the national convention of the National Negro Business League. She began her speech “I want briefly to speak of the opportunities offered the women of our race in the florist business. This is a big, undeveloped field…it is one of the most profitable enterprises a woman can engage in.” Mrs. Weaver called her profession “as healthful as it is interesting.”

Indeed, her work as a florist was healthful and interesting, but it was also meaningful as both a service to Black communities and a way for African American women to make a living. While Bessie Weaver wasn’t the first florist and floriculturist, she was a part of a history and future of Black women entrepreneurs who made money with flowers and foilage.

Anna Parkes (Athens, Georgia) told her WPA interviewer, “Old Marster had a big fine gyarden. His Negroes wukked it good, and us wuz sho’ proud of it. Us lived close in town, and all de Negroes on de place wuz yard and house servants. Us didn’t have no gyardens ’round our cabins, kaze all of us et at de big house kitchen. Ole Miss had flowers evvywhar ’round de big house, and she wuz all time givin’ us some to plant ’round de cabins.” Mrs. Parkes describes a plantation life that didn’t include food gardens in the quarters but rather flower gardens, which leaves more questions than answers. However, the care of the land’s floriculture is a theme found at many plantations and urban sites of enslavement. (Two examples can be found at James Madison’s Montpelier Plantation and the Governor’s Palace gardens in Colonial Williamsburg.)

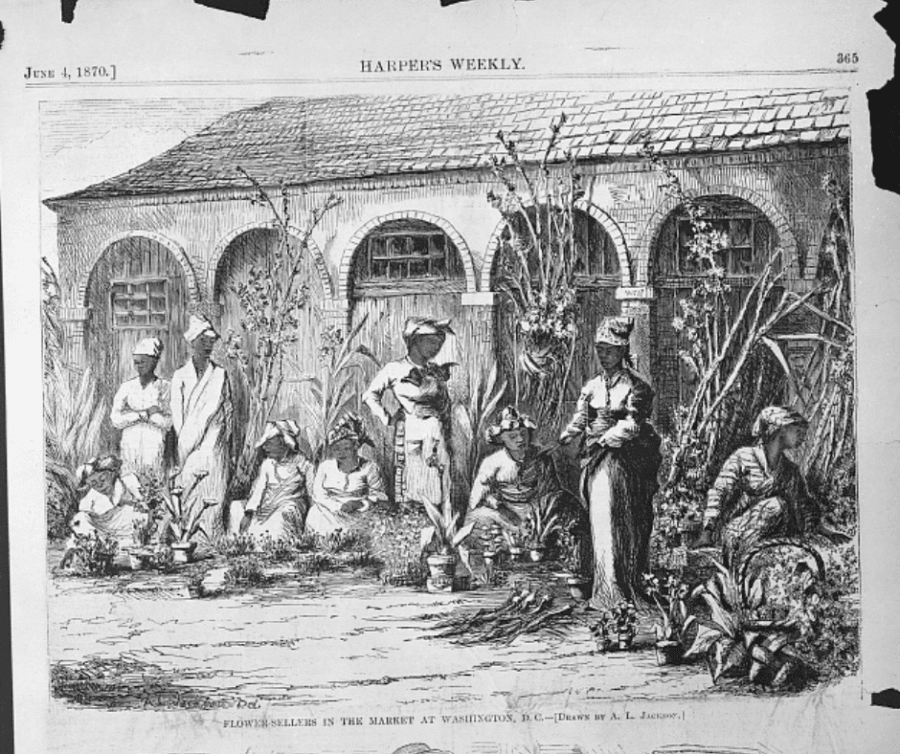

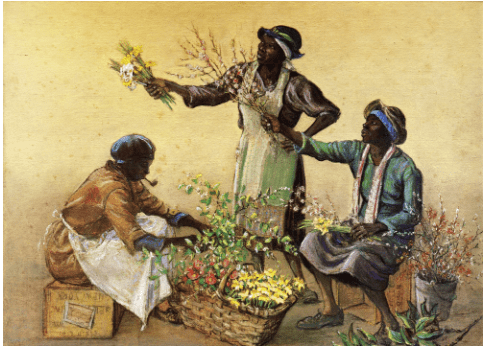

It was probably the same knowledge and proximity to flowers that enabled Black women (free and enslaved) to find economic opportunity as flower vendors around the country. They could be found selling flowers in urban centers marketplaces such as Boston, Memphis, New York City, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, Richmond and Charleston, SC.

cx The practice would extend beyond emancipation and it is safe to say that it was a precursor to Black women becoming floral shop and flower nursery owners. There was also a power exerted by Black women flower vendors – a control of their agency as income-earners and influencers – that either infuriated people or delighted them. In cities, like Charleston, where “the flower ladies” crowded street corners selling their wares, nearby merchants complained about them being a nuisance. Ally Bush (Charleston Magazine) wrote, “Despite various other restrictions, the flower ladies persisted and became iconic, appearing in magazines, such as National Geographic in 1939, and on postcards. Today, African American artisans still sell their goods—such as sweetgrass baskets and popcorn-berry wreaths—at the Four Corners of Law.”

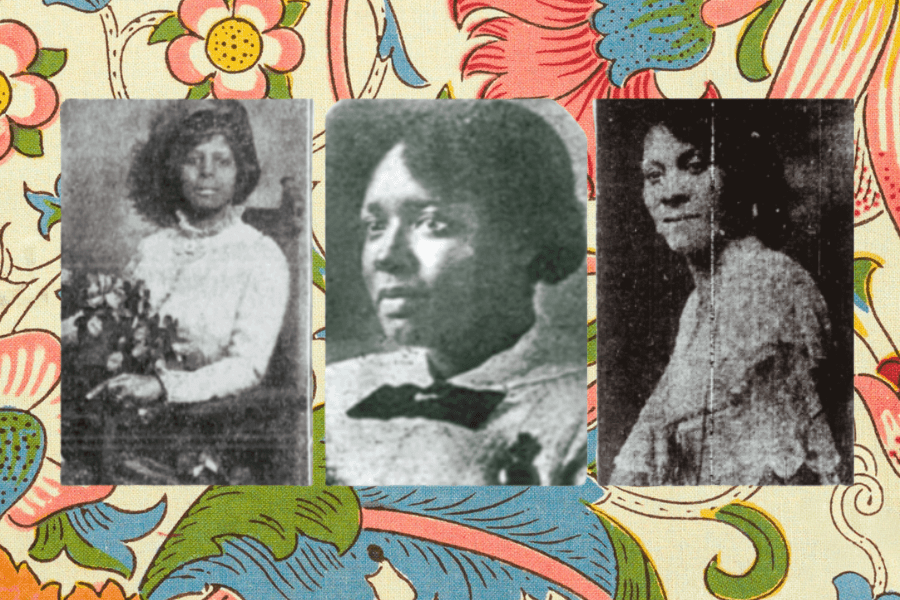

While these enterprising women were only trying to make a living using what was available, they also received discouragement and criticism from people who looked like them but owned floral houses. An “us” and “them” mentality existed as a form of marketing the benefits of buying from Black floral shop and nursery owners, who often took to Black newspapers to assert their superiority over the street vendors.The elitism mirrored the elitism of some white-owned florist shops, which were mostly owned by men who only hired men to make floral arrangements and work in nurseries. But that isn’t the part of the story that should prevail. There were also allies, Black women like Bessie Weaver (Kansas City, MO), Annie Vann Reid (Darlington, SC) and Blanche Hurston (Jacksonville, FL and Zora Neale Hurston’s sister-in-law) were advocates and educators, who encouraged Black women like the flower ladies to scale their businesses.

All three women operated their own greenhouses and flower gardens, which enabled them to sell their flowers in a shop. They knew what most male florists would not say out loud: Floral businesses were easy to begin, because it involved little to no investment. Annie Vann Reid believed in educating women on the business of floriculture, but also educating them about creating beautiful home gardens. She is quoted for saying, “I began cautiously on a small scale… I found the soil fertile and willing to yield.”

Weaver, Hurston and Reid share a similar story to the many Black women who owned floral shops around the country. The ways in which their businesses survived were many. There were women who opened floral shops next to funeral homes and hotels to market to a clientele who would need them for weddings and deaths. For a number of years, African American florists were discriminated against in the telefloral industry (think FTD), so they invented their own solutions thanks to the leadership of James Heard, a NYC florist, who created the International Florists Association. Black newspapers like the Chicago Defender had directories of florists, speaking to the industry’s expansion in Black communities nationwide.

Fast forward to now, and Black women florists continue to work with the same energy and passion as their predecessors. In 2020, Atlanta florist and event planner Valerie Crisostomo created a digital showcase called “Black Girl Florists.” Her showcase and directory convey the versatility and tradition of Black women in floristry and floriculture. Some of these women, including Valerie, are doing things that Bessie, Blanche and Annie envisioned for the future.

Stacie Lee Banks & Kristie Lee Jones are the third generation owners and operators of Lee’s Flower and Card Shop in Washington, DC, which was founded by their grandparents in 1945. Nailah Marie, owner of Blessed Up Blooms, is a florist/farmer and chef in Atlanta, GA.

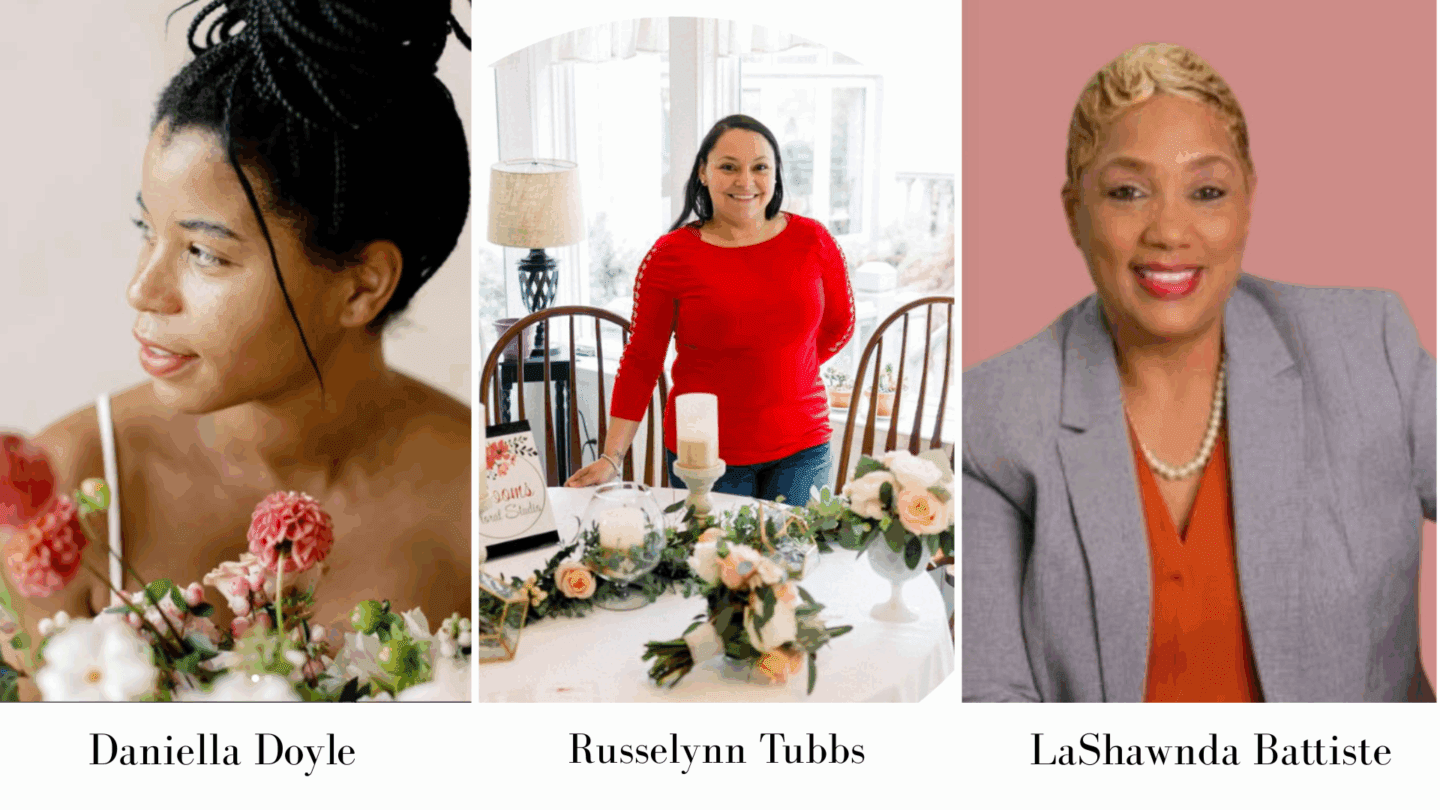

Daniella Doyle owns Salt+Stem Flower Co. (she has a vintage F100 flower truck too) in Charleston, SC. Russelynn Tubbs is the owner of Blooms Floral Studio in Carrollton, Kentucky. Columbus, Ohio’s Battiste LaFleur Galleria is an 80+ years old, family-owned floral business that began in South Carolina; sisters LaShawnda (pictured) and Vera Battiste oversee the business along with the rest of the family.

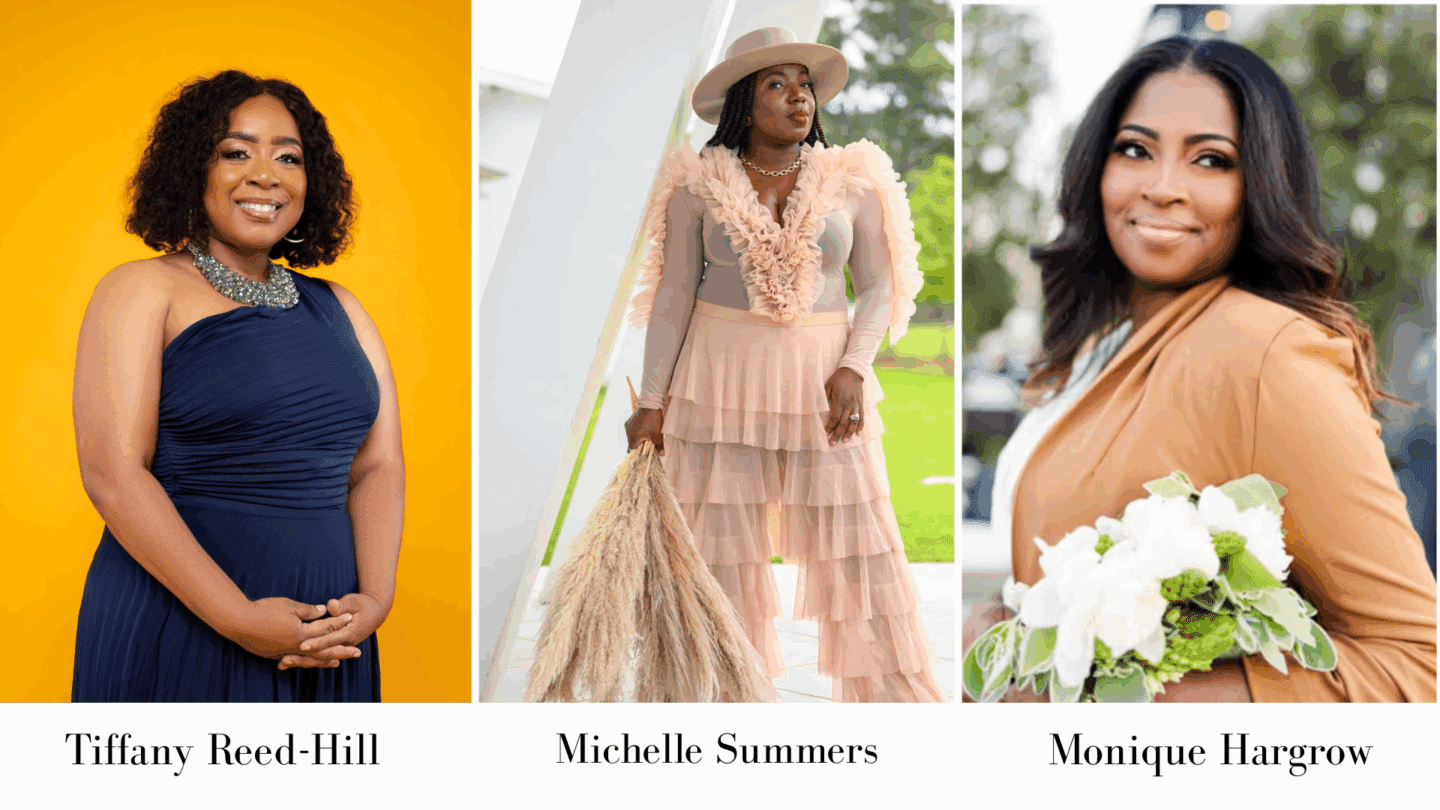

Tiffany Reed-Hill of Memphis, TN is the owner of Hill Co 12 Event Designs and her designs involve florals. Michelle Summers of Herby’s Flower Shop in Summerville, SC is a heritage floral designer with a deep respect for lowcountry and Gullah traditions. And Monique Hargrow owns Bee’s Blossoms Floral Design in Jacksonville, FL and a fitting tribute to Blanche Hurston as both an entrepreneur and lover of flowers.

If you are looking for a Black florist to support in your area, then visit Black Girl Florists’ directory. Perhaps, you’re interested in becoming a florist, then reach out to Valerie and any of the other florists mentioned. We need more beauty in our worlds. 💐