They needed protection from angry white men who protested against their hiring and the firing of 300 white men, women and children. In what we would call a business scaling, the president of Charleston Cotton Mill decided that their workforce needed more experience and people who would work for less pay. Firing most of the white laborers and hiring twenty Black women, as spinners and weavers, was the solution. Integrating the mill was not a social experiment. It was profit engineering. But, what made the hiring of these women remarkable is that it took place in 1897, long before progressives and labor unions put the pressure on cotton manufacturers to integrate. And long before other large southern textile mills even considered hiring Blacks for anything other than the backbreaking work.

“Why should a people who are skilled in the use of the needle, who help to build our houses and till our fields, who can learn to play the piano and ride the bicycle—why should such a people not be able to learn to mind the machinery in a cotton mill?” News and Courier, 1897

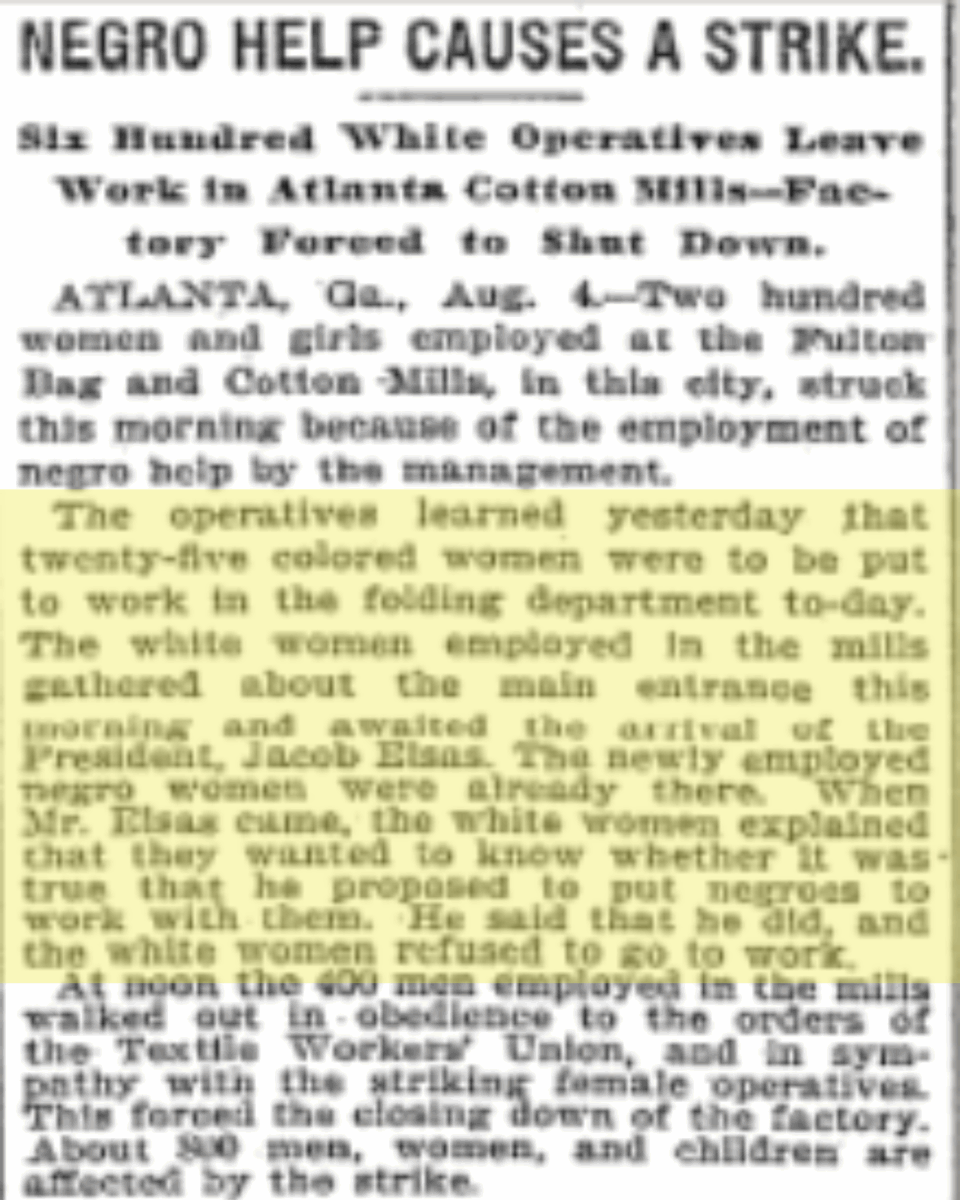

According to the Lowcountry Digital History Initiative (LDHI), the owners of Atlanta Mills in Georgia attempted to do the same thing in 1897. “At almost the same time, in August 1897, Atlanta Mills in Atlanta, Georgia hired a few black workers to fill out its workforce. Fifteen hundred white workers went on strike to protest the presence of just eight black women—and unlike the Charleston protesters, they succeeded in having all the black women dismissed.” On August 5, 1897, the New York Times reported the incident.

While the same was not true in Charleston, the women suffered great threat of harm causing their husbands, fathers, brothers and boyfriends to gather at the end of the day to protect them. There were a few skirmishes between the Black men and white protesters, who also felt their women and children needed to be protected. Ultimately, the company hired security guards.

There was another important slight these women experienced. The mill allowed a Methodist church affiliated organization to run a kindergarten on the premises. The organization refused to serve the children of Black mothers working at the mill.

By 1899, the Charleston Cotton Mills Company went bankrupt and was sold at auction to J.H. Montgomery and Seth Milliken. They renamed it Vesta Cotton Mills and endeavored to use nothing but “Negro” labor. The new owners appealed to local Black clergy to screen applicants for “good workers” who would show up every day and work the long hours. But they had another ideal candidate, according to LDHI, “The company actively recruited mixed-race applicants, who were thought to have a stronger work ethic; Montgomery later boasted to the Philadelphia Inquirer that ‘the big majority of our pupil-employees had an admixture of white blood in their veins.’”

It didn’t work. The mill closed in 1900 and moved to Gainesville, Georgia. A lot of blame was tossed around. Some blamed the African Americans who worked there. The Boston Evening Transcript (January 5, 1901) wrote a story about Vesta’s closing that said, “Negro Labor a Failure,” implying the workers were lazy and unreliable. South Carolina’s governor and other politicians blamed Vesta owners and treated the closing as an embarrassment. Booker T. Washington weighed in on the closing in an article for Gunton’s Magazine, where he made a veiled attempt to defend the mill’s Black workers while alleviating some of the owners’ guilt. And Black clergy in Charleston blamed the closing on the owners’ failure to keep promises such as providing housing, and pay decent wages to the Black women (and men) who worked at the mill.

The building that housed the mill would ultimately become a successful cigar factory that survived for several decades. It survived with both Black and white laborers. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and once was the home of Johnson and Wales culinary school.

Sadly, for all we know about the mill, its owners, the city and the building, we know less about the twenty brave women who made textile industry history. They are not identified by name.

Primary source of information: Susan Millar Williams et al for the Lowcountry Digital History Intiative