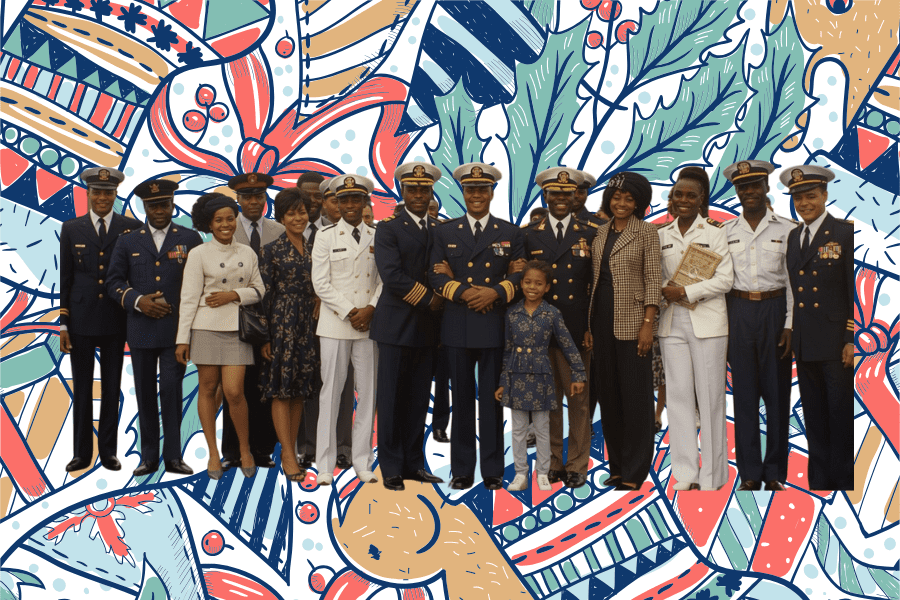

There’s always cause to celebrate whenever a soldier returns home for a holiday, at the end of a tour of duty or at the end of a war. Among those celebrating the return of Black soldiers were their families – blood and chosen – and their communities, which also included their churches and other institutions. Some of the celebrations were intimate and private while others were public.

In the 1980s, there were two belated public celebrations for Black soldiers. One was for Vietnam veterans, which was coordinated by two Black women veterans. The other was for the Black troops who served in the Civil War. It was a reburial ceremony for members of the 55th and 55th from Massachusetts. They were buried with military honors in the national cemetery in Beaufort, SC. Wynton Marsalis played “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and Morgan Freeman was a pallbearer.

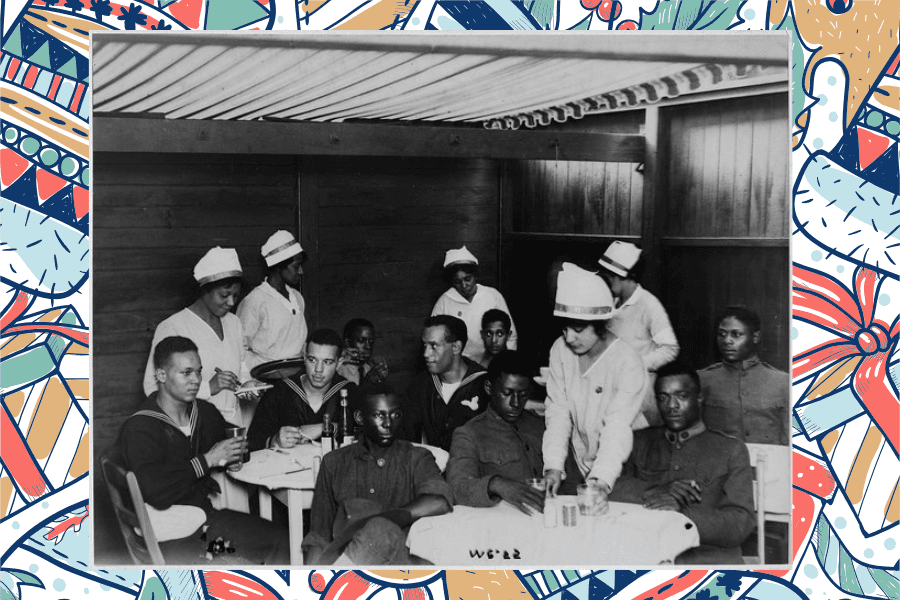

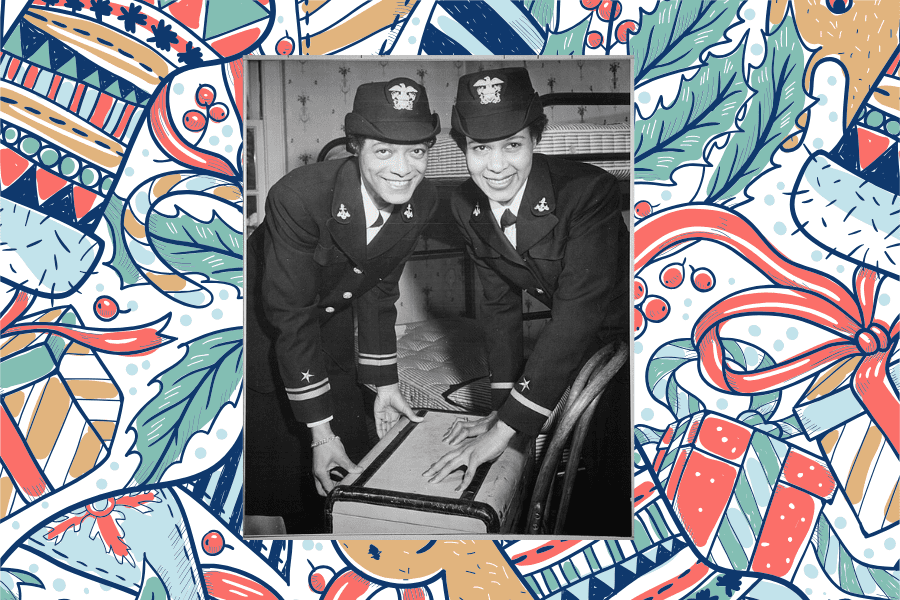

Many of the earlier celebrations were held under segregated circumstances. After the Civil War, USCT veterans were excluded from public celebrations, leaving community organizers to create their own for Black veterans. That tradition would continue until the U.S. military was desegregated by President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order 9981, signed on July 26, 1948. Even after E.O. 9981 became law, it would take some time before official military celebrations were fully desegregated.

However, desegregation didn’t stop Black communities from welcoming home troops with enthusiasm and thanksgiving.

On May 10, 1991, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Colin Powell was a grand marshal for the Gulf War veterans parade in Chicago. General Powell, along with an estimated 300,000 citizens, welcomed troops home. According to UPI, “Nine military and 29 high school bands marched down the more than mile-long parade route, along with more than 100 floats and 20,000 veterans from 70 organizations.” The celebration was as much a celebration for returning soldiers as it was for those who lost their lives, their families, and veterans from previous wars. Bishop Arthur M. Brazier, pastor of Chicago’s Apostolic Church of God and WW II veteran, was a part of the program. And it was a celebration of Powell, who was the highest ranking military official in the United States.

In 2003, another type of homecoming celebration took place in Columbia, SC. Army Specialist Shoshana Johnson was returning to the United States after being held prisoner in Iraq for 22 days along with five other members of her unit. On April 13, 2003, she was freed by the Marine Corp. Johnson was the first U.S. Black female prisoner of war on foreign soil. She enlisted to be a food service specialist and retired a decorated veteran. On the day of her release, she was greeted by her aunt Celia and cousin Michael. She’d been shot in both ankles so she began convalescence with another aunt. But between her parents’ home and the homes of extended family, Johnson received a hero’s welcome from both the public and her (multi-generational military) family. Neighborhoods raised welcome banners, and neighbors of kin sent flowers. She was awarded medals: The Presidential Unit Citation, Bronze Star, Purple Heart and the Prisoner of War Medal. She was feted by Congress, the Congressional Black Caucus and more. But the one reception she wanted more than anything involved being welcomed by her family “in true American style, with a family bar-b-que.”

The act of celebrating Black soldiers and service personnel is more than an act of protocol. For centuries, Black communities have used these celebrations to say thank-you to its veterans, to amplify patriotism and support people who care about the security of this country and the future of all citizens.

The celebrations differed depending on the circumstances, but whatever the case, we have always expressed gratitude for our sons and daughters who have served in the military during time of war and time of peace.

0